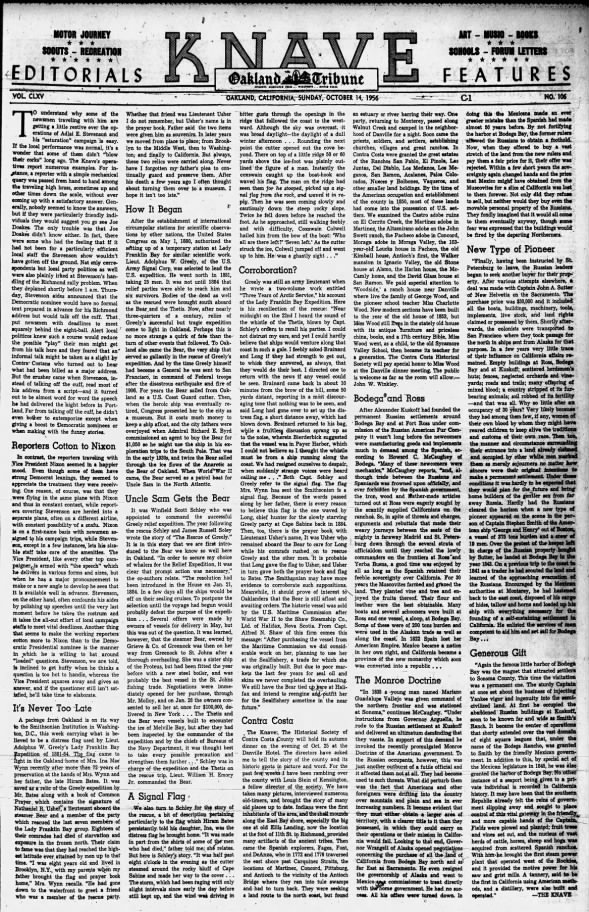

I've left out the first few paragraphs, which are current events of October, 1956. You can read them in the clipping at the bottom of this page. - MF

It's Never Too Late

A package from Oakland is on its way to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.Ç., this week carrying what is believed to be a distress flag used by Lieut. Adolphus W. Greely's Lady Franklin Bay Expedition of 1881-84. The flag came to light in the Oakland home of Mrs. Ina Mae Wynn recently after more than 72 years of preservation at the hands of Mrs. Wynn and her father, the late Hiram Bates. It was saved as a relic of the Greely expedition by Mr. Bates along with a book of Common Prayer which contains the signature of Nathaniel R. Usher, a lieutenant aboard the steamer Bear and a member of the party which rescued the last seven members of the Lady Franklin Bay group. Eighteen of their comrades had died of starvation and exposure in the frozen north. Their claim to fame was that they had reached the highest latitude ever attained by men up to that time. "I was eight years old and lived in Brooklyn, N.Y., with my parents when my father brought the flag and prayer book home," Mrs. Wynn recalls. "He had gone down to the waterfront to greet a friend who was a member of the rescue party. Whether that friend was Lieutenant Usher I do not remember, but Usher's name is in the prayer book. Father said the two items were given him as souvenirs. In later years we moved from place to place; from Brooklyn to the Middle West, then to Washington; and finally to California. But always, these two relics were carried along. Never have I forgotten my father's plea to continually guard and preserve them. After his death a few years ago I often thought about turning them over to a museum. I hope it isn't too late."

How It Began

After the establishment of international circumpolar stations for scientific observations by other nations, the United States Congress on May 1, 1880, authorized the setting up of a temporary station at Lady Franklin Bay for similar scientific work. Lieut. Adolphus W. Greely, of the U.S. Army Signal Corp, was selected to lead the U.S. expedition. He went north in 1881, taking 25 men. It was not until 1884 that relief parties were able to reach him and six survivors. Bodies of the dead as well as the rescued were brought south aboard the Bear and the Thetis. Now, after nearly three-quarters of a century, relics of Greely's successful but tragic expedition come to light in Oakland. Perhaps this is no more strange a quirk of fate than the turn of other events that followed. To Oakland also came the Bear, the very ship that served so gallantly in the rescue of Greely's expedition. And by the time Greely himself had become a General he was sent to San Francisco, in command of Federal troops after the disastrous earthquake and fire of 1906. For years the Bear sailed from Oakland as a U.S. Coast Guard cutter. Then, when the heroic ship was eventually retired, Congress presented her to the city as a museum. But it costs much money to keep a ship afloat, and the city fathers were overjoyed when Admiral Richard E. Byrd commissioned an agent to buy the Bear for $1,050 so he might use the ship in his exploration trips to the South Pole. That was in the early 1930s, and twice the Bear sailed through the ice flows of the Antarctic as the Bear of Oakland. When World War II came, the Bear served as a patrol boat for Uncle Sam in the North Atlantic.

Uncle Sam Gets the Bear

It was Winfield Scott Schley who was appointed to command the successful Greely relief expedition. The year following the rescue Schley and James Russell Soley wrote the story of “The Rescue of Greely." It is in this story that we are first introduced to the Bear we know so well here in Oakland. "In order to secure my choice of whalers for the Relief Expedition, it was clear that prompt action was necessary,” the co-authors relate. “The resolution had been introduced in the House on Jan. 21, 1884. In a few days all the ships would be off on their sealing cruises. To postpone the selection until the voyage had begun would probably defeat the purpose of the expedition ... Several offers were made by owners of vessels for delivery in May, but this was out of the question. It was learned, however, that the steamer Bear, owned by Grieve & Co. of Greenock was then on her way from Greenock to St. Johns after a thorough overhauling. She was a sister ship of the Proteus, but had been fitted the year before with a new steel boiler, and was probably the best vessel in the St. Johns fishing trade. Negotiations were immediately opened for her purchase, through Mr. Molloy, and on Jan. 28 the owners consented to sell her at once for $100,000, delivered in New York ... The Thetis and the Bear were vessels built to encounter the ice of Melville Bay, but after they had been inspected by the commander of the expedition and by the chiefs of Bureaus of the Navy Department, it was thought best to take every possible precaution and strengthen them further ...” Schley was in charge of the expedition and the Thetis on the rescue trip. Lieut. William H. Emory Jr. commanded the Bear.

A Signal Flag

We also turn to Schley for the story of the rescue, a bit of description pertaining particularly to the flag which Hiram Bates persistently told his daughter, Ina, was the distress flag he brought home. "It was made in part from the shirts of some of the men who had died," father told me, she relates. But here is Schley's story. "It was half past eight o'clock in the evening as the cutter steamed around the rocky bluff of Cape Sabine and made her way to the cover ... The storm, which had been raging with only slight intervals since early the day before still kept up, and the wind was driving in bitter gusts through the openings in the ridge that followed the coast to the westward. Although the sky was overcast, it was broad daylight - the daylight of a dull winter afternoon ... Rounding the next point the cutter opened out the cove beyond. There on top of a little ridge 50 or 60 yards above the ice-foot was plainly outlined the figure of a man. Instantly the coxswain caught up the boat-hook and waved his flag. The man on the ridge had seen them for he stooped, picked up a signal flag from the rock, and waved it in reply. Then he was seen coming slowly and cautiously down the steep rocky slope. Twice he fell down before he reached the foot. As he approached, still walking feebly, and with difficulty, Coxswain Colwell hailed him from the bow of the boat: 'Who all are there left?' 'Seven left. As the cutter struck the ice, Colwell jumped off and went up to him. He was a ghastly sight..."

Corroboration?

Greely was still an army lieutenant when he wrote a two-volume work entitled "Three Years of Arctic Service," his account of the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition. Here is his recollection of the rescue: "Near midnight on the 22nd I heard the sound of the whistle of the Thetis, blown by Capt. Schley's orders to recall his parties. I could not distrust my ears, and yet I could hardly believe that ships would venture along that coast in such a gale. I feebly asked Brainard and Long if they had strength to get out, to which they answered, as always, that they would do their best. I directed one to return with the news if any vessel could be seen. Brainard came back in about 10 minutes from the brow of the hill, some 50 yards distant, reporting in a most discouraging tone that nothing was to be seen, and said Long had gone over to set up the distress flag, a short distance away, which had blown down. Brainard returned to his bag, while a fruitless discussion sprang up as to the noise, wherein Bierderbick suggested that the vessel was in Payer Harbor, which I could not believe as I thought the whistle must be from a ship running along the coast. We had resigned ourselves to despair, when suddenly strange voices were heard calling me ..." Both Capt. Schley and Greely refer to the signal flag. The flag Mrs. Wynn has sent the Smithsonian is a signal flag. Because of the words passed along by her father, there is every reason to believe this flag is the one waved by Long, chief hunter for the slowly starving Greely party at Cape Sabine back in 1884. Then, too, there is the prayer book, with Lieutenant Usher's name. It was Usher who remained aboard the Bear to care for Long while his comrades rushed on to rescue Greely and the other men. It is probable that Long gave the flag to Usher, and Usher in turn gave both the prayer book and flag to Bates. The Smithsonian may have more evidence to corroborate such suppositions. Meanwhile, it should prove of interest to Oaklanders that the Bear is still afloat and awaiting orders. The historic vessel was sold by the U.S. Maritime Commission after World War II to the Shaw Steamship Co., Ltd. of Halifax, Nova Scotia. From Capt Alfred N. Shaw of this firm comes this message: "After purchasing the vessel from the Maritime Commission we did considerable work on her, planning to use her at the Sealfishery, a trade for which she was originally built. But due to poor markets the last few years for seal oil and skins we never completed the overhauling. We still have the Bear tied up here at Halifax and intend to reengine and outfit her for the Sealfishery sometime in the near future."

Contra Costa

The Knave: The Historical Society of Contra Costa County will hold its autumn dinner on the evening of Oct. 25 at the Danville Hotel. The directors have asked me to tell the story of the county and its historic spots in picture and word. For the past few weeks I have been rambling over the county with Louis Stein of Kensington, a fellow director of the society. We have taken many pictures, interviewed numerous old-timers, and brought the story of many old places up to date. Indians were the first inhabitants of the area, and the shell mounds along the East Bay shore, especially the big one at old Ellis Landing, now the location at the foot of 11th St. in Richmond, provided many artifacts of the ancient tribes. Then came the Spanish explorers, Fages, Font, and DeAnza, who in 1772 and 1776 traversed the east shore past Carquinez Straits, the locations of Martinez, Concord, Pittsburg, and Antioch to the vicinity of the Antioch Bridge where they ran into tule swamps and had to turn back. They were seeking a land route to the north coast, but found an estuary or river barring their way. One party, returning to Monterey, passed along Walnut Creek and camped in the neighborhood of Danville for a night. Soon came the priests, soldiers, and settlers, establishing churches, villages and great ranchos. In Contra Costa were granted the great estates of the Ranchos San Pablo, El Pinole, Las Juntas, Del Diablo, Los Medanos, Los Meganos, San Ramon, Acalanes, Palos Colorados, Nueces y Bolbones, Vaqueros, and other smaller land holdings. By the time of the American occupation and establishment of the county in 1850, most of these lands had come into the possession of U.S. settlers. We examined the Castro adobe ruins on El Cerrito Creek, the Martinez adobe in Martinez, the Altamirano adobe on the John Swett ranch, the Pacheco adobe in Concord, Moraga adobe in Moraga Valley, the 103-year-old Loucks house in Pacheco, the old Kimball house, Antioch's first, the Walker mansion in Ignacio Valley, the old Stone house at Alamo, the Harlan house, the McCamly home, and the David Glass house at San Ramon. We paid especial attention to 'Woodside,' a ranch house near Danville where live the family of George Wood, and the pioneer school teacher Miss Charlotte Wood. New modern sections have been built to the rear of the old house of 1853, but Miss Wood still lives in the stately old house with its antique furniture and priceless china, books, and a 17th century Bible, Miss Wood went, as a child, to the old Sycamore Valley School, then became its teacher for a generation. The Contra Costa Historical Society will pay special honor to Miss Wood at the Danville dinner meeting. The public is welcome as far as the room will allow - John W. Winkley.

Bodega and Ross

After Alexander Kuskoff (Ivan Kuskov?) had founded the permanent Russian settlements around Bodega Bay and at Fort Ross under commission of the Russian American Fur Company it wasn't long before the newcomers were manufacturing goods and implements much in demand among the Spanish, according to Howard C. McCaughey of Bodega. "Many of these newcomers were mechanics." McCaughey reports, "and, although trade between the Russians and Spaniards was frowned upon officially, and ever forbidden by the Spanish government, the iron, wood and leather-made articles turned out at Ross were eagerly sought by the scantily supplied Californians on the ranchos. So, in spite of threats and charges, arguments and rebuttals that made their weary journeys between the seats of the mighty in faraway Madrid and St. Petersburg down through the several strata of officialdom until they reached the lowly commanders on the frontiers at Ross and Yerba Buena, a good time was enjoyed by all as long as the Spanish retained their feeble sovereignty over California. For 30 years the Muscovites farmed and grazed the land. They planted vine and tree and enjoyed the fruits thereof. Their flour and leather were the best obtainable. Many boats and several schooners were built at Ross and one vessel, a sloop, at Bodega Bay. Some of these were of 200 tons burden and were used in the Alaskan trade as well as along the coast. In 1822 Spain lost her American Empire. Mexico became a nation in her own right, and California became a province of the new monarchy which soon was converted into a republic ...

The Monroe Doctrine

"In 1835 a young man named Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo was given command of the northern frontier and was stationed at Sonoma," continues McCaughey. "Under instructions from Governor Arguella, he rode to the Russian settlement at Kuskoff and delivered an ultimatum demanding that they vacate. In support of this demand he invoked the recently promulgated Monroe Doctrine of the American government. To the Russian occupants, however, this was just another outburst of a futile official and it affected them not at all. They had become used to such threats. What did perturb them was the fact that Americans and other foreigners were drifting into the country over mountain and plain and sea in ever increasing numbers. It became evident that they must either obtain a larger area of territory, with a clearer title to it than they possessed, in which they could carry on their operations or their mission in California would fail. Looking to that end, Governor Wrangell of Alaska opened negotiations concerning the purchase of all the land of California from Bodega Bay north and as far East as Sacramento. He even resigned the governorship of Alaska and went to Mexico as a commissioner to treat directly with the home government. He had no success. All his offers were turned down. In doing this the Mexicans made an ever greater mistake than the Spanish had made almost 50 years before. By not fortifying the harbor at Bodega Bay, the former rulers allowed the Russians to obtain a foothold. Now, when they offered to buy a vast stretch of the land from the new rulers and pay them a fair price for it, their offer was rejected. Within a few short years the sovereignty again changed hands and the price that Mexico might have obtained from the Muscovites for a slice of California was lost to them forever. Not only did they refuse to sell, but neither would they buy even the movable personal property of the Russians. They fondly imagined that it would all come to them eventually anyway, though some fear was expressed that the buildings would be fired by the departing Northerners.

New Type of Pioneer

"Finally, having been instructed by St. Petersburg to leave, the Russian leaders began to seek another buyer for their property. After various attempts elsewhere, a deal was made with Captain John A. Sutter of New Helvetia on the Sacramento. The purchase price was $30,000 and it included all the boats, buildings, machinery, tools, implements, live stock, and land rights claimed or possessed by them. Shortly afterwards, the colonists were transported to San Francisco where they took passage for the north in ships sent from Alaska for that purpose. In a few years very little trace of their influence on California affairs remained. Empty buildings at Ross, Bodega Bay and at Kuskoff; scattered herdsmen's huts; fences, neglected orchards and vineyards; roads and trails; many offspring of mixed blood; a country stripped of its fur-bearing animals; soil robbed of its fertility - and that was all. Why so little after an occupancy of 30 years? Very likely because they had among them few, if any, women of their own blood by whom they might have reared children to keep alive the traditions and customs of their own race. Then too, the manner and circumstance surrounding their entrance into a land already claimed and occupied by other white men marked them as merely sojourners no matter how sincere were their original intentions to make a permanent settlement. Under those conditions it was hardly to be expected that they would plan for the future and bring home builders of the gentler sex from far away Russia. Hardly had the Russians cleared the horizon when a new type of pioneer appeared on the scene in the person of Captain Stephen Smith of the American ship 'George and Henry' out of Boston, a vessel of 375 tons burden and a crew of 19 men. Over the protest of the keeper left in charge of the Russian property bought by Sutter, he landed at Bodega Bay in the year 1843. On a previous trip to the coast in 1841 as a trader he had scouted the land and learned of the approaching evacuation of the Russians. Encouraged by the Mexican authorities at Monterey, he had hastened back to the east coast, disposed of his cargo of hides, tallow and horns and loaded up his ship with everything necessary for the founding of a self-sustaining settlement in California. He enlisted the services of men competent to aid him and set sail for Bodega Bay...

Generous Gift

"Again the famous little harbor of Bodega Bay was the magnet that attracted settlers to Sonoma County. This time the visitation was a permanent one. The sturdy Captain at once set about the business of injecting Yankee vigor and ingenuity into the semi-civilized land. At first he occupied the abandoned Russian buildings at Kuskoff, soon to be known far and wide as Smith's Ranch. It became the center of operations that shortly extended over the vast domain of eight square leagues that, under the name of the Bodega Rancho, was granted to Smith by the friendly Mexican government. In addition to this, by special act of the Mexican legislature in 1845, he was also granted the harbor of Bodega Bay. No other instance of a seaport being given to a private individual is, recorded in California history. It may have been that the southern Republic already felt the reins of government slipping away and sought to place control of this vital gateway in the friendly, and more capable hands of the Captain. Fields were plowed and planted; fruit trees and vines set out, and the nucleus of vast herds of cattle, horses, sheep and hogs was acquired from scattered Spanish ranchos. With him he brought the first steam power plant that operated west of the Rockies, and it provided the motive power for his saw and grist mills. A tannery, said to be the first in California using American methods, and a distillery, were also built and operated."

Comments

Post a Comment