The Ohlone: An Archaeological Park In Bay Area

JOANN DEAN, Ranger

East Bay Region Parks

On the eastern shore of South San Francisco Bay rised a miniature mountain

range aptly named Coyote Hills. Now considered "Land-islands," masses of

greenstone and chert rock surrounded by sediment 600 feet deep, the Coyote

Hills were surrounded by Bay waters at one point in their geologic history,

and as recently as 1917, by a marshy delta fed by Alameda Creek.

The rich food resources of marshes and mudflats, the mild climate, and the

proximity of oak-covered foothills made this an area ideal for human

habitation, and the first Californians had settled here long before

Europeans set foot upon this bountiful land. By the time the Portola

expedition "discovered" San Francisco Bay in 1769, Indian villages were

scattered all along the Alameda Creek flood plain.

The village sites were the scene of all activities of domestic life. Births

occurred and deaths (the mourners buried their dead near, or sometimes in,

the clay floors of their circular tule-thatched homes). Food - oysters,

snails and other shellfish from San Francisco Bay, salmon from Alameda

Creek, acorns and game from the Coast Ranges - was prepared and eaten and

the remains discarded near the eating place. Tools of stone and bone for

hunting, fishing, home-building, basket-making, food preparation and other

tasks were manufactured, broken and discarded.

|

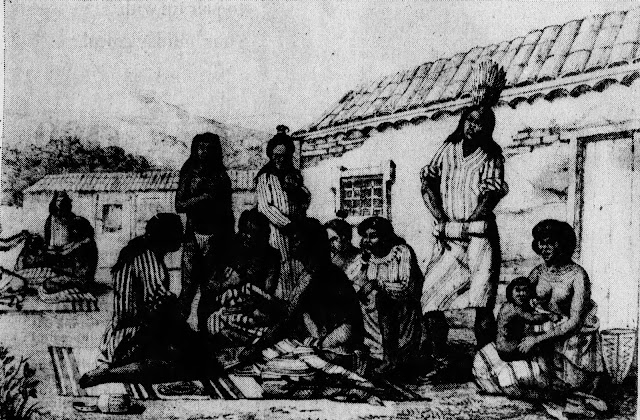

| Group of California Indians sitting on a blanket playing a game with bundles of sticks held in the hand. After a drawing by Louis Choris, about 1818. Both drawings are from the Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives, Bureau of American Ethnology Collection. |

In time, the debris formed mounds which grew in elevation with each passing

generation, until they rose above the surrounding flood plain. Hence was

formed the history book of a people who had no written language, and who

lived in balance with their environment for 3,000 to 4,000 years.

But history was not kind to these first Bay Area residents. Their fate, like

that of all native Americans, was foretold in the creation myth of the

Yumans, a southern California tribe:

"We are the ancient people, the older, darker people. And because we are

older, we know that nothing ever stays the same... Now into our land has

come a younger, lighter people, and because they are young, they want to

take everything they see. They will take our lands, and we will go hungry.

We are the older, darker people; we know how to die. We hope the younger,

lighter people will know how to live."

The younger, lighter people, not satisfied with decimating the Indian

population, went on to destroy even the traces of that ancient civilization.

And the destruction continues today. It is estimated that a former Indian

site a day is lost in California. Out of 425 sites recorded in the Bay Area

during the early 1900's, few are undisturbed. In the Newark-Fremont area,

for instance, the unearthing of ancient bones and tools is fairly common

during construction of housing developments, roads and shopping centers. And

in our progress-oriented culture, few contractors or private land-owners are

willing to stop construction to save remnants of a civilization which has

been replaced.

|

| Headdresses of California Indians, from a lithograph after a drawing by Louis Choris, made in the San Francisco Bay area, about 1818. |

There is one place in southern Alameda County, however, where time can stand

still and catch its breath. Coyote Hills Regional Park, a cooperative

venture between the two-county East Bay Regional Park, and the Alameda

County Flood Control District, includes in its 1,000 acres four Indian

"shellmounds" typical of village sites already lost. These invaluable sites

have been saved so that citizens of the future may learn from the past.

Although the two larger sites were recorded in the early 1900's, when Coyote

Hills and the flood plain directly east of them formed the Patterson Ranch,

the true value of the sites went unrecognized. Until the 1940's, the

shellmounds were treated as merely slight rises in a monotonously flat

plain. A ranch house was erected on one: another was cut in half during the

construction of an irrigation ditch. The upper 18 inches of all four, the

precious last pages in the history book, were disturbed annually by plowing,

and much of their meaning was lost.

Starting in 1949, however, archaeologists from several Bay Area State

Colleges - chiefly, San Jose, San Francisco and Hayward - began excavating

the sites. In the next twenty years, exploratory trenches were dug in sites

Ala-12, Ala-13, and Ala-329, and full-scale excavation was begun in Ala-328

(at 13 feet the largest shellmound in the East Bay after the 30 foot deep

Emeryville mound was covered by an auto graveyard).

One-third of Ala-328 was excavated by college classes, and a wealth of

artifacts was uncovered. Several packed clay floors of long-decayed houses

were discovered. Broken tools of many uses - elk antler wedges, obsidian and

chert spear points, deer-bone drills, blakers and sweat-scrapers,

acorn-grinding mortars and pestles, to name a few - were found. Five hundred

skeletons, with associated artifacts - shell beads, charmstones, tools and

food needed in the next life, were painstakingly removed from the site.

The pattern of occurrence of certain artifact types was noted and compared

to those of other excavated shellmounds. In this way, it was determined that

the site was inhabited continually, except between about 400 and 800 A.D.,

and finally abandoned about 1200 A.D. Shellfish was favored as a main food

source during the earlier period, with game becoming more and more thportant

as the shoreline moved further and further from the village site. Theories

on burial, hunting and other social customs were advanced, with inferences

drawn from excavated materials.

With the full cooperation of the land owner, Mr. Patterson, the

archaeologists worked steadily, compromising thoroughness for speed in the

hope of competing excavation before this site, too, became a victim of

progress. In 1967, the portion of Patterson Ranch containing the shellmounds

was purchased as part of the Alameda Creek Flood Control Project. The East

Bay Regional Park District bought the adjacent hills and opened the area to

the public on May 23, 1968.

With the possible destruction of the mounds no longer a threat, the

archaeologists relaxed. The next two years saw more time consuming projects,

such as an inch by inch analysis of changes in food habits, carried out

using the shell-mounds as a research resource. Old worries were traded for

new, however, with the influx of park visitors. Vandalism of the shellmounds

increased. Uninformed souvenir collectors often carried off shells by the

pocketful, and hard-core "pot-hunters" were not satisfied until they could

take "real Indian bones" from their resting places for display in their

private collections. To protect the sites, it was necessary to erect chain

link fences around them.

Today, archaeologists themselves have decided to discontinue excavation of

the sites, in order to put their efforts into rescue operations on sites

which are not in protected public ownership. Eventually, the value of the

Coyote Hills Mounds may lie in their being the only unexcavated

archaeological sites left in Alameda County.

Excavation has ceased, but the use of the sites as an educational tool

continues. Past meets present almost every day of the week as East Bay

Regional Park District naturalists "read the history book" of the Ohlone

Indians for the family, school and youth groups.

The newest addition to the staff is Tony Tonemah, a Kiowa Indian, born and

raised on his father's farm in Oklahoma. Tony has spent the past several

weeks immersing himself in the pre-history of his California contemporaries,

and now joins the naturalists in conducting tours of the shellmounds and

other points of interest in the park.

Persons wishing to take advantage of this service may call 862-2244 for the

times a family tours or an appointment for school and youth groups.

Comments

Post a Comment