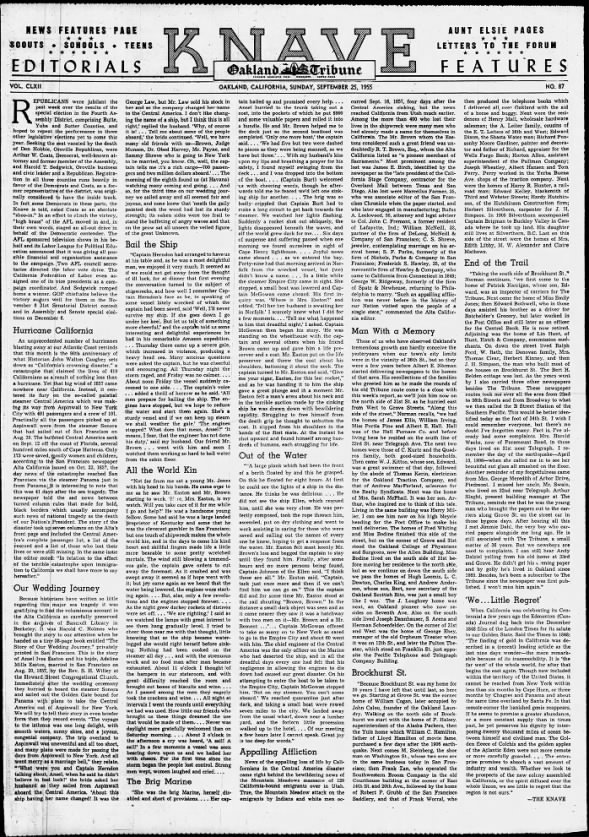

Knave: sinking of "Central America" in 1857 - Albert E. Norman reminisces about his neighborhood - gold rush in London Times, 1848 - Oakland Tribune - 25 Sep 1955

I'm leaving out the first few paragraphs, which deal with current politics, and moving right to the histories and stories. Click the clipping below if you want to read what you missed, here. The Central America has been in the news lately, as its precious cargo of gold - from California - is up for auction.- MF

Hurricane California

An unprecedented number of hurricanes blasting away at our Atlantic Coast reminds that this month is the 98th anniversary of what Historian John Walton Caughey sets down as "California's crowning disaster," a catastrophe that claimed the lives of 419 Californians as a result of nothing less than a hurricane. Yet that big wind of 1857 came nowhere near California. Instead, it centered its fury on the so-called palatial steamer Central America which was making its way from Aspinwall to New York City with 491 passengers and a crew of 101. Practically all the passengers picked up at Aspinwall were from the steamer Sonora that had sailed out of San Francisco on Aug. 20. The buffeted Central America sank on Sept. 12 off the coast of Florida, several hundred miles south of Cape Hatteras. Only 173 were saved, mostly women and children, according to the San Francisco newspaper Alta California issued on Oct. 23, 1857, the day news of the catastrophe reached San Francisco via the steamer Panama just in from Panama. It is interesting to note that this was 41 days after the sea tragedy. The newspaper told the sad news between turned column rules that made for bold, black borders which usually accompany such news of national tragedy as the death of our Nation's President. The story of the disaster took up seven columns on the Alta's front page and included the Central America's complete passenger list, a list of the rescued and a list of, those who lost their lives or were still missing. In the same issue the editor noted: "In relation to the effect of the terrible catastrophe upon immigration to California we shall have more to say hereafter."

Our Wedding Journey

Because historians have written so little regarding this major sea tragedy it was gratifying to find the voluminous account in the Alta California so carefully preserved in the archives of Bancroft Library in Berkeley. It was Harold C. Holmes who brought the story to our attention when he handed us a tiny 38-page book entitled "The Story of Our Wedding Journey," privately printed in San Francisco. This is the story of Ansel Ives Easton and his bride, Adeline Mills Easton, married in San Francisco on Aug. 20, 1857, by the Rev. S. H. Willey at the Howard Street Congregational Church. Immediately after the wedding ceremony they hurried to board the steamer Sonora and sailed out the Golden Gate bound for Panama with plans to take the Central America out of Aspinwall for New York. We will try to tell their story in even briefer form than they record events. "The voyage to the isthmus was one long delight, with smooth waters, sunny skies, and a joyous, congenial company. The trip overland to Aspinwall was uneventful and all too short, and many plans were made for passing the days from Aspinwall to New York. And all went merry as a marriage bell," they relate. "What were you and Captain Herndon talking about, Ansel, when he said he didn't believe in bad luck?' the bride asked her husband as they sailed from Aspinwall aboard the Central America. 'About this ship having her name changed! It was the George Law, but Mr. Law sold his stock in her and so the company changed her name to the Central America. I don't like changing the name of a ship, but I think this is all right,' replied the husband. 'Why, of course it is!... Tell me about some of the people aboard,' the bride continued. "Well, we have many old friends with us - Brown, Judge Munson, Dr. Obed Harvey, Mr. Payne, and Sammy Shreve who is going to New York to be married, you know. Oh, well, the captain tells me it's a rich cargo - 700 passengers and two million dollars aboard.'... The morning of the eighth found us (at Havana) watching many coming and going. . . . And so, for the third time on our wedding journey we sailed away and all seemed fair and joyous, and none knew that 'neath the gaily painted deck the wood had lost its sturdy strength; its oaken sides were too frail to stand the buffeting of angry waves and that on the prow sat all unseen the veiled figure of the great Unknown.

Bail the Ship

"Captain Herndon had arranged to have us at his table and, as he was a most delightful man, we enjoyed it very much. It seemed as if we could not get away from the thought of ill luck, for at dinner that first evening the conversation turned to the subject of shipwrecks, and how well I remember Captain Herndon's face as he, in speaking of some vessel lately wrecked of which the captain had been saved, said 'Well, I'll never survive my ship. If she goes down I go under her keel. But let us talk of something more cheerful,' and the captain told us some interesting and delightful experiences he had in his remarkable Amazon expedition. ... Thursday there came up a severe gale, which increased in violence, producing a heavy head sea. Many anxious questions were asked the captain, but he was cheerful and encouraging. All Thursday night the storm raged, and Friday was no calmer. . . . About noon Friday the vessel suddenly careened to one side. . . . The captain's voice ... added a thrill of horrow as he said. 'All men prepare for bailing the ship. The engines have stopped, but we hope to reduce the water and start them again. She's a sturdy vessel and if we can keep up steam we shall weather the gale.' 'The engines stopped? What does that mean, Ansel?' 'It means, I fear, that the engineer has not done his duty,' said my husband. Our friend Mr. Brown ... went with him and soon I watched them working so hard to bail water from the cabin floor.

All the World Kin

"Not far from me sat a young Mr. Jones with his head in his hands. He came over to me as he saw Mr. Easton and Mr. Brown starting to work. 'Here, Mrs. Easton, is my watch. Will you take care of it for me while I go and help?' He was a handsome young fellow. Some had said he was a large landed proprietor of Kentucky and some that he was the cleverest gambler in San Francisco; but one touch of shipwreck makes the whole world kin, and in the days to come his kind heart and skillful fingers made life a little more bearable to some pretty wretched mortals. The wind still blowing a tremendous gale, the captain gave orders to cut away the foremast. As it crashed and was swept away it seemed as if hope went with it; but joy came again as we heard that the water being lowered, the engines were starting again.... But, alas, only a few revolutions and the engines stopped forever.... As the night grew darker rockets of distress were set off.... 'We are righting,' I said as we watched the lamps with great interest to see them hang gradually level. I tried to cheer those near me with that thought, little knowing that as the ship became water-logged she would right herself before sinking. Nothing had been cooked on the steamer all day... and with the strenuous work and no food man after man became exhausted. About 11 o'clock I thought of the hampers in our stateroom, and with great difficulty reached the room and brought out boxes of biscuits and wine. As I passed among the men they eagerly took the crackers and wine. ... All night at intervals I went the rounds until everything we had was used. How little our friends who brought us these things dreamed the use that would be made of them.... Never was daylight more gratefully welcomed than on Saturday morning. . . . About 2 o'clock in the afternoon a cry was heard, 'A sail! A sail!' In a few moments a vessel was seen bearing down upon us and we hailed her with cheers. For the first time since the storm began the people lost control. Strong men wept, women laughed and cried....

The Brig Marine

"She was the brig Marine, herself disabled and short of provisions.... Her captain hailed us and promised every help.... Ansel hurried to the trunk taking out a coat, into the pockets of which he put $900 and some valuable papers and rolled it into a bundle. He and Mr. Brown helped me to the deck just as the second boatload was completed. 'Only one more boat,' the captain said.... 'We had five but two were dashed to pieces as they were being manned, so we have but three.' ... With my husband's kiss upon my lips and breathing a prayer for his safety, I found myself swinging from the deck... and I was dropped into the bottom of the boat. . . . (Captain Burt) welcomed us with cheering words, though he afterwards told me he feared we'd left one sinking ship for another. . . . The brig was so badly crippled that Captain Burt had to make a long circuit to get back towards the steamer. We watched her lights flashing. Suddenly a rocket shot out obliquely, the lights disappeared beneath the waves, and all the world grew dark for me.... Six days of suspense and suffering passed when one morning we found ourselves in sight of Cape Henry lighthouse. . . . Joyful news came aboard . . . as we entered the bay. Forty-nine had that morning arrived in Norfolk from the wrecked vessel, but (we) didn't know a name. . . . In a little while the steamer Empire City came in sight. She stopped, a small boat was lowered and Captain McGowan came aboard. His first inquiry was, 'Where is Mrs. Easton?' and added, 'Tell her her husband is awaiting her in Norfolk.' I scarcely knew what I did for a few moments. ... 'Tell me what happened to him that dreadful night,' I asked. Captain McGowan then began his story. 'He was standing on the wheelhouse with the captain and several others when his friend Brown came up and gave him a life preserver and a coat. Mr. Easton put on the life preserver and threw the coat about his shoulders, buttoning it about the neck. The captain turned to Mr. Easton and said, "Give me your cigar, Easton, for this last rocket," and as he was handing it to him the ship gave a great plunge and in a moment Mr. Easton felt a man's arms about his neck and in the terrible suction made by the sinking ship he was drawn down with bewildering rapidity. Struggling to free himself from the death grip he thought to unbutton the coat. It slipped from his shoulders in the hands of the first mate. At the instant he shot upward and found himself among hundreds of humans, each struggling for life.

Out of the Water

"A large plank which had been the front of a berth floated by and this he grasped. On this he floated for eight hours. At first he could see the lights of a ship in the distance. He thinks he was delirious. ... He did not see the ship Ellen, which rescued him, until she was very close. He was perfectly composed, took the rope thrown him, ascended, put on dry clothing and went to work assisting in caring for those who were saved and calling out the names of every one he knew, hoping to get a response from the water. Mr. Easton felt most keenly Mr. Brown's loss and begged the captain to stay until they found him. Finally, after some hours and no more persons being found, Captain Johnson of the Ellen said, "I think these are all." Mr. Easton said, "Captain, tack just once more and then if we can't find him we can go on." This the captain did and for some time Mr. Easton stood at the rail shouting "Brown, Brown." In the distance a small dark object was seen and as it came nearer they saw it was a hatchway with two men on it - Mr. Brown and a Mr. Bement ...... Captain McGowan offered to take as many on to New York as cared to go in the Empire City and about 60 went with him. The chief engineer of the Central America was the only officer on the Marine who had deserted the ship, and in all the dreadful days every one had felt that his negligence in allowing the engines to die down had caused our great disaster. On his attempting to enter the boat to be taken to the Empire City, Captain McGowan stopped him. 'Not on my steamer. You can't come aboard.' We reached quarantine just after dark, and taking a small boat were rowed seven miles to the city. We landed away from the usual wharf, down near a lumber yard, and the forlorn little procession walked up to the hotel.... Of our meeting a few hours later I cannot speak. Great joy is too deep for words."

Appalling Affliction

News of the appalling loss of life by Californians in the Central America disaster came right behind the bewildering news of the Mountain Meadows massacre of 120 California-bound emigrants over in Utah. True, the Mountain Meadow attack on the emigrants by Indians and white men occurred Sept. 16, 1857, four days after the Central America sinking, but the news reached California from Utah much earlier. Among the more than 400 who lost their lives in the shipwreck were many men who had already made a name for themselves in California. The Mr. Brown whom the Eastons considered such a great friend was undoubtedly R. T. Brown, Esq., whom the Alta California listed as "a pioneer merchant of Sacramento." Most prominent among the lost was James E. Birch, identified by the newspaper as the "late president of the California Stage Company, contractor for the Overland Mail between Texas and San Diego. Also lost were Marcellus Farmer, 35, who was associate editor of the San Francisco Chronicle when the paper started, and who later engaged in manufacturing; Rufus A. Lockwood, 50, attorney and legal adviser to Col. John C. Fremont, a former resident of Lafayette, Ind.; William McNeill, 33, partner of the firm of DeLong, McNeill & Company of San Francisco; C. S. Shreve, [Should be S. S. Shreve.] jeweler, contemplating marriage on his arrival home; S. F. Parke, formerly of the firm of Nichols, Parke & Company in San Francisco; Frederick S. Hawley, 35, of the mercantile firm of Hawley & Company, who came to California from Connecticut in 1849; George W. Ridgeway, formerly of the firm of Spatz & Newhouse, returning to Philadelphia to marry. "Such an appalling affliction was never before in the history of our Nation visited upon the people of a single state," commented the Alta California editor.

This next section was interesting. The words are the recollection of a kid's memory, with names known from delivering newspapers. Due to all the misspellings of names, this was likely due to the names being passed on orally, from resident to Albert to the writer. Using a combination of census, map and city directories on genealogy web sites, plus newspaper archives allowed me to figure out who these people were. A subsequent telling of the story of the neighborhood, by Albert, also clears things up. - MF

Man With a Memory

Those of us who have observed Oakland's tremendous growth can hardly conceive the yesteryears when our town's city limits were in the vicinity of 36th St., but so they were a few years before Albert E. Norman [obituary, this blog, more, more] started delivering newspapers to the homes of that area. His recollections of the families who greeted him as he made the rounds of his old Tribune route come to a close with this week's report, so we'll join him now on the north side of 31st St. as he hurried east from West to Grove Streets. "Along this side of the street," Norman recalls, "we had the homes of James Ellis, William Irving, Miss Portia Pine and Albert E. Hall. Hall was of the Hall Furnace Co. and before living here he resided on the south line of 33rd St. near Telegraph Ave. The next two homes were those of C. Kurtz and the Quadros family, both good-sized households. Then came W. J. Kittoo, [I think this is Kitto] whose son, Edward, was a great swimmer of that day, followed by the abode of Thomas Kerin, electrician for the Oakland Traction Company, and that of Andrew MacFarland, salesman for the Realty Syndicate. Next was the home of Mrs. Sarah McPhail. [Grace Elaine (Miler) McPhail] It was her son, Arthur, [More from Arthur] who inspired me to think of this tale. Living in the same building was Harry Miller. I can see him now on his high bicycle heading for the Post Office to make his mail deliveries. The homes of Fred Whiting and Miss Bodine [Mary E. (Tiffany) Baudin] finished this side of the street, but on the corner of Grove and 31st stood the Oakland College of Physicians and Surgeons, now the Allen Building. Miss Bodine lived on the south side of 31st before moving her residence to the north side, but as we continue on down the south side we pass the homes of Hugh Loomis, L. C. Dowton, Charles King, and Andrew Anderson, whose son, Bert, now secretary of the Oakland Scottish Rite, was just a small boy like I was. The J. Loughrey [James F. Loughery] home was next, an Oakland pioneer who now resides on Seventh Ave. Also on the south side lived Joseph Dannhauser, S. Arena and Herman Schoenfelder. On the corner of 31st and West was the home of George Ebey, manager of the old Orpheum Theater when it was on 12th St., and later the Fulton Theater, which stood on Franklin St. just opposite the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company Building.

Some images from the 1910 census, with these names:

|

| United States Census, 1910, page 27 |

.jpg) |

| United States Census, 1910, page 28 |

Brockhurst St.

"Because Brockhurst St. was my home for 20 years I have left that until last, so here we go. Starting at Grove St. was the corner home of William Cogan, later occupied by John Calou, [Pierre Calou, as far as I can tell.] founder of the Oakland Laundry. Walking on the north side of Brockhurst we start with the home of P. Halsey [Peter Lars Halse] superintendent of the Alaska Packers, then the Yule [Youle] home which William C. Hamilton, father of Lloyd Hamilton of movie fame, purchased a few days after the 1906 earthquake. Next comes M. Steinberg, the shoe man on Washington St., whose two sons are in the same business today in San Francisco; then Frank Zan, [Jennie F. Zan was at 660 Brockhurst in 1910. A familysearch record for her] who operated the Southwestern Broom Company in the old Courthouse building at the corner of East 14th St. and 20th Ave., followed by the home of Robert P. Grubb of the San Francisco Saddlery, and that of Frank Worral, who then produced the telephone books which I delivered all over Oakland with the aid of a horse and buggy. Next were the residences of Henry Mall, [Henry C. Mell] wholesale hardware salesman; ["Worrall eventually sold this house to H. C. Mell."] the A. Leiter family, cousins of the E. T. Leiters of 36th and West; Edward Dixon, the Shasta Water man; Richard Ponsonby Moore Gardiner, painter and decorator and father of Richard, appraiser for the Wells Fargo Bank; Horton Allen, assistant. superintendent of the Pullman Company; Joseph Wheatley, [directory] Albert Hansen and Tom Perry. [Thomas H. Parry] Perry worked in the Yerba Buena Ave. shops of the traction company. Next were the homes of Harry R. Hunter, [Harry L. Hunter] a railroad man; Edward Kelley, blacksmith of Third and Webster Streets; Hardy Hutchinson, of the Hutchinson Construction firm; Herbert Silverthorn, [Herbert Cecil Silverthorne] carpenter for J. H. Simpson. In 1905 Silverthorn accompanied Captain Brigman to Buckley Valley in Canada where he took up land. His daughter still lives at Silverthorn, B. C. Last on this side of the street were the homes of Mrs. Edith Libby, M. W. Alexander [daughter Ruby Alexander?] and Claire Mathews.

End of the Trail

"Taking the south side of Brockhurst St.," Norman continues, "we first come to the home of Patrick Harrigan, whose son, Edward, was an inspector of carriers for The Tribune. Next came the home of Miss Emily Jones; then Edward Bothwell, [Edwin Dwight Bothwell] who in those days assisted his brother as a driver for Batchelder's Grocery, but later worked in the Post Office and still later as an officer for the Central Bank. He is now retired. Adjoining was the home of Lin Hunt, [Joseph Lynn Hunt] of Hunt, Hatch & Company, commission merchants. On down the street lived Ralph Ford, W. Rath, the Donovan family, [Interesting, John Donovan is the father of Jennie F. Zan, perhaps this is the link to Frank Zan, above.] Mrs. Thomas Clear, Herbert Kinney, [Horace Robert Kinney] and then J. H. Simpson, the man who built most of the houses on Brockhurst St. The Bert H. Belden cottage was last. As the years went by I also carried three other newspapers besides The Tribune. These newspaper routes took me over all the area from 22nd to 36th Streets and from Broadway to what we then called the B Street Station of the Southern Pacific. [here?] This would be better identified today as the foot of 34th St. I wish I could remember everyone, but there's no doubt I've forgotten many. Fact is, I've already had some complaints. Mrs. Harold Wachs, now of Paramount Road, in those days lived on 31st near Telegraph. I remember the day of the earthquake - April 18, 1906 - when she called me in to see her beautiful cut glass all smashed on the floor. Another reminder of my forgetfulness came from Mrs. George Meredith of Arbor Drive, Piedmont. I missed her uncle, Mr. Swain, who lived on 32nd near Telegraph. Arthur Slaght, present building manager at The Tribune, reminds me that he was the young man who brought the papers out to the carriers along Grove St. on the street car in those bygone days. After hearing all this I met Jimmie Dahl, the very boy who carried papers alongside me long ago. He is still associated with The Tribune, a small matter of 36 years. But we newsboys are used to complaints. I can still hear Andy Dalziel yelling from his old home at 33rd and Grove. He didn't get his evening paper and by golly he's lived in Oakland since 1865. Besides, he's been a subscriber to The Tribune since the newspaper was first published. I won't miss him again."

'We... Little Regret'

When California was celebrating its Centennial a few years ago the Edmonton (Canada) Journal dug back into the December 1848 files of the London Times for its salute to our Golden State. Said the Times in 1848: "The finding of gold in California was described in a (recent) leading article as the last nine days wonder-the more remarkable because of its inaccessibility. It is 'the far west' of the whole world, for after that begins the east again. Though now included within the territory of the United States, it cannot be reached from New York within less than six months by Cape Horn, or three months by Chagres and Panama and about the same time overland by Santa Fe. In that remote corner the banished genie reappears. If he seems to promise a greater abundance, or a mor, goe constant supply than in times past, he yet preserves his dignity by interposing twenty thousand miles of ocean between himself and civilized man. The Golden fleece of Colchis and the golden apples of the Atlantic Eden were not more remote or more carefully guarded. . . . The enterprise promises to absorb a vast amount of industry and wealth. Whether we look to the prospects of the new colony assembled in California, or the spirit diffused over the whole Union, we see little to regret that the region is not ours."

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment