When San Francisco Was Teaching America to Ride a Bicycle - Sun, Feb 26, 1905 - Page 5 - San Francisco Chronicle

It Was San Francisco Which First Took Up the Odd Invention Called a Boneshaker and Brought It and the Taller Bicycle Which Came After It Into Popular Usage; Thus San Francisco Paved the Way for the Modern Safety and the Automobile...

PIONEER cyclists! Like their hardy forbears of old, the men who hewed down forests, forded impassable streams and generally opened the way to civilization, their tale is one of difficulties overcome, of obstacles which they refused to recognize, of lukewarm assistance in time of need, and of final triumph which has given to San Francisco the right to be hailed as "First Expounder of the Wheel."

|

|

HERMAN C. EGGERS WHOSE MILE RECORD STOOD FOR FIVE YEARS |

This now well-known and universal sport had its origin far back in the '60s, when people were first startled and then amused by the appearance on the streets of an odd arrangement of wheels and steering gear, known to the initiated as a velocipede, and whose principal use seemed to be to cause unlimited enjoyment for small boys and to frighten unwary steeds. This instrument, not of torture, but of fright, consisted of two iron-rimmed woodenwheels, thirty-six to forty inches in diameter, with a crank adjusted to thefront axle, which apparatus afterward became the nucleus of modern safety wheels.

First Velocipedes in San Francisco.

These velocipedes, or "boneshakers," as they came to be called when brought into general use, were first introduced into this country by the famous Hanlon Brothers, the originators of the triple flying trapeze, who on one of their tours carried with them two velocipedes upon which trick riding was done. [See also, Hanlon Brothers to being Velocipede racing to New Orleans. 31 Dec 1868. and The Hanlons have introduced the Parisian novelty of velocipedes upon the American stage. - MF] This act of trick riding was a great novelty, and attracted the attention of athletes all over the country, and more especially of certain members of the Olympic Club, San Francisco. A few of these men persuaded the Hanlons to bring their velocipedes to the clubrooms, and here to the intense amusement of those who witnessed the endeavor, George H. Strong, W. F. Lawton and several others tried hard to rival the acrobats in their proficiency with the wheel. The scene was equal to a modern comedy show, but it was the inception of modern bicycling in the West and practically in the United States.

|

|

COL. R. De CLAIRMONT FATHER OF CYCLING PRESIDENT OF SAN FRANCISCO'S FIRST CLUB |

Colonel Ralph Clairmont, [Ralph de Clairmont] the veteran velocipedist, tricyclist and bicyclist, known as the "Father of Cycling of the Pacific Coast," and now secretary of the Orpheum, nods his white head reminiscently when asked the date of the introduction of the first velocipede in San Francisco for individual use.

"It was back in '68," he tells you. "And I have ridden for thirty-five years." When the question was put, "And you ride still, Colonel?" his eye lit up and his face beamed as he answered, “Every morning, when the weather permits. Ah, it is a marvelous pastime, I assure you, Madame." He will also tell you proudly, "I have the finest wheel in the country. It is an English model, and a magnificent machine."

For several years after the introduction of the first velocipede the Colonel possessed the only wheel on the Coast. Then a San Francisco firm began to manufacture them, and as the number of "freaks," as they were dubbed, increased, the first stumbling block in the way of their pleasure came into view. They were not to be allowed to ride upon the sidewalks!

Here, then, was the situation. Velocipedes with wooden wheels and iron rims, and streets paved with cobbles!

A Pavilion for Riders.

At this juncture, an enterprising business man bethought himself of the old Mechanics Pavilion, at that time occupying what is now known as Union Square. The lease of that large building, with its extensive smooth floors, and a charge of general admission to the owners of velocipedes for use of this floor ought to prove a good financial scheme. It was tried, and plucked success from threatened discomfiture, for there were frequently over a hundred clumsy riders, endeavoring to steer a wobbly machine over a slippery floor, and contusions and black eyes were things of no comment in those "try-again” days.

The large posts which supported the gallery on either side were Waterloos, where many a novice, met his ruin. To attempt to steer between them was to run the dangers of Scylla and Charybdis. The floor at one end of the building was lower than at the other, which fact but added to the impetus with which the luckless riders skimmed toward disaster, but despite all premonitions and prognostications of woe there were those whose ambition caused them to soar still farther toward the stars. In the center of the pavilion was a fountain that had been used in beautifying the place upon former gala occasions, but which the lessee of the building, with an eye to business, had bridged over with a narrow planking which extended in a vertical direction, over the crest of the fountain and ran down again on the other side. Several ambitious riders were anxious to court good luck by ascending to the summit of this plashing pool, and in olden times would doubtless have put forth a prayer to Neptune before making the assault; for to extricate oneself from the whirling, wheeling throng, mount the doubtful bridge, and, on the other side, rejoin the cycling crowd without a "spill," was certainly, it not a work of art, willingly accounted one of science. Frequently, though, time was made, and good time too, for notwithstanding wooden wheels, five-inch crank, inclined floor and malevolent posts to dodge, L. Getchell made a mile in three minutes and forty seconds. an unparalleled record, considering the conditions.

This phase of wheeling continued for over a year, when the American restlessness asserted itself, and the first outdoor run was planned, with the Cliff House as its far distant goal.

The Pioneer Cyclers were keen on the sport, the air and bright sunshine lent an added zest to their anticipated pleasure, and all alive with jollity and good nature they started on the great trial. A few hours later the sad tale had been told. The cyclers, accompanied by their dilapidated wheels, returned ignominiously in an express wagon! Of a smooth surface, the wheels were almost useless.

From that ride dated the decline of the old "boneshakers." Eventually, the pavilion was closed, and wheels stored away in attics and barns until rescued by the enterprising small boy.

Then the trouble began! The sidewalks were claimed by both aspiring youth and pedestrians. The petition presented to the Oakland Council at that time, and signed by 1500 people, gives an idea of the attitude taken by pedestrians. The petition reads:

Boneshakers Banished by Law.

“It is hereby declared unlawful for any person or persons to ride a velocipede or any other two-wheeled vehicle upon any street, sidewalk, alley or byway within the corporate limits of the city of Oakland.”

On this condition of affairs entered the high and phantom-like wheel, known then as the bicycle, but recalled now as the "old Ordinary" or "Neckbreaker.” This remarkable wheel made its first bow to the public at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. The model was an English one, possessing a driving wheel eight feet in diameter. The rider was compelled to mount from a box, and ascend two or three steps on his backbone before he could gain the seat. But in spite of the gigantic proportions of the wheel, and the difficulty of attaining the saddle, that wheel introduced the entire wheel family.

First Tall Bicycle Came Here,

Again to the “Father of Cycling” fell the distinction of first possession on the Pacific Coast. In 1876, Colonel de Clairmont imported from France the first high wheel to become the property of an individual rider. This was one of three on the entire continent, and compared with the bungling iron-rimmed wheels of the past, these tall and stately machines seemed like strayed giraffes as they meandered solemnly through the streets.

The driving wheel ranged from 48 to 60 inches, according to the height of the rider. Above the front wheel, fastened to the front fork were the handle bars, from which projected an iron backbone which wound around the circumference of the driving wheel and terminated in a small 15-inch wheel.

If the bicycle possessed an iron backbone, it required nothing less than a backbone of steel added to an unlimited amount of courage merely to mount, let alone to ride this machine. It was not an uncommon sight to behold beginners hopping unsteadily for about fifty feet upon one leg, making repeated efforts to gain the tiny step-wheel, and it required a full-fledged acrobat to accomplish this feat gracefully; nevertheless, the silent steed, once conquered, offered unlimited possibilities for sport of the swiftest kind. The old wooden spokes had been superseded by glittering steel ones, iron rims by rubber tires, the driving-wheel enlarged and the hind one diminished. These changes were conducive to far greater speed attained with far less exertion. The rider's new position, too, gave him better control of the machine, the seat being directly over the axis, thus producing a propelling motion almost identical with that of walking.

In 1877 two wheels were imported into this country, from Coventry, England, by G. Loring Cunningham and were placed on exhibition in the window of a carpet store on Bush street. They were of the Bayless & Thomas make, and proved an excellent advertisement for the house, for they became a nine days wonder. One of these wheels Mr. Cunningham kept for his personal use; the other was purchased by George H. Strong, although the cost of it was twice that of one of our modern wheels, the price ranging from $130 upward.

|

|

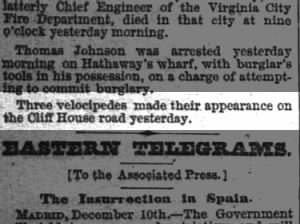

S. F. BICYCLE CLUB AND GUESTS ON A RUN IN GOLDEN GATE PARK, JULY 1883 |

Prominent Men Learned to Ride.

Gradually the sport gained ground. New wheels were imported, first by individuals, and then by well-known firms. Colonel de Clairmont's enthusiasm was still unbounded and he numbered among his pupils such men as George C. Perkins, George Hobe, George Cunningham; Herman C. Eggers and several others. The waning enthusiasm of these men which had received a temporary check in their disgust with the old style of wheel, the "Boneshaker," returned and all the keenness of interest in the sport revived with the possession of the new "Neckbreakers." Wheeling was destined to become the leading sport, but the cyclers of to-day with their softly cushioned seats and tires find the difficulties and obstacles with which the pioneer wheelmen were forced to contend almost incredible recitals in the face of the ease with which their swift wheels speed along the roads made specially for them to-day.

In truth, the obstacles were almost insurmountable. In Oakland the ordinance forbidding the use of velocipedes was still in vogue. The wheels must be carried or carted to the extreme limits before their enjoyment could be procured; while in San Francisco the streets were paved with cobbles and as the wheels were large and unwieldy, riding over this unaccommodating surface was fraught with danger. A "header" from the high elevation of the "Neckbreaker" was sure to result in serious injury, while that innocent appearing hind wheel, without any apparent provocation, was apt to soar suddenly, skyward, pitching the hapless rider some twenty feet ahead of his machine.

In front of the Palace Hotel was, at that time, a little patch of asphalt which the untiring athletes were loth to depart from, except when their wheels developed a will of their own. This was the sole spot where the devotees of the sport destined to world-wide renown, could practice their difficult art. No back alleys in which to hide the graceful failures of beginners! Nothing but the most public of public thoroughfares, where one must assume the role of star performer for the benefit of a partly admiring, partly jeering public. The stare of gaping crowds, the curses poured out upon them by the drivers of horses, who took fright at the singular apparitions, were among the lesser tribulations endured by the pioneer wheelmen of San Francisco.

Park Bars "Infernal Machines."

Golden Gate Park with its desirable roads was the goal of these wheelmen's desires, and from time to time emissaries were sent to the Park Commissioners to convince them that the Park was an eminently suitable place in which to gratify their needs, but these dignitaries refused without preamble to have the beautiful fairness of the drives spoiled by the presence of the "Infernal machines."

Then the "club" resort was had. On December 13, 1878, a club was formed known as the San Francisco Bicycle Club, which was the first organization of its kind on the Coast, and the second in the whole United States. Among the members were Governor George C. Perkins, Colonel Ralph de Clairmont, Judge Kerrigan, George H. Strong, G. Loring Cunningham, F. G. Blinn, J. G. Golby, George Hobe, Robert M. Welch, Charles L. Barrett, F. C. Merrill, [maybe F. T. Merrill] E. Mohrig. F. E. Osbourne, Charles C. Moore, Fred Russ Cook, Herman C. Eggers, Frank D. Elwell and many others.

In the face of the united and determined efforts of this club the barriers of further progress in the science of wheeling were broken down. The Oakland barrier fell to the lot of George H. Strong, a resident of the city which completely ostracized the sport, and his task was not an easy one. To have an ordinance repealed, and one which thoroughly voiced the sentiments of the people, required much persuasion and a deal of delicate electioneering even to break the ice of the subject. However, with the aid of Ex-Mayor Pardee, father of the present Governor, and Henry Vrooman, an amendment was drawn up allowing the wheelmen the privilege of the streets which were practically out in the suburbs, such as the streets north of Twelfth, and down across the Twelfth-street bridge to the county road.

During following years many new riders entered the new field for sport, and a new ordinance was passed which granted all the privileges enjoyed by the wheelmen of today. Next Golden Gate Park was again attacked. This argument involved too long a time for the sportsmen and there were those among them who fell sadly from grace, haying their wheels carted to a secluded spot by an expressman, dropped over the fence, where the owners were eagerly awaiting their arrival, who then enjoyed the felicity of veritable "stolen sweets."

Eventually, a committee from the San Francisco Bicycle Club, composed of Governor George C. Perkins, Colonel de Clairmont, George Hobe and Columbus Waterhouse, was successful in obtaining an audience with the Park Commissioners, when the greatest surprise was manifested by the potentates as the committee made known its errand.

“Do you mean to say that you have formed a club of wheelmen?" was the astounded query. To them, it seemed too ridiculous to be true.

But a concession was finally obtained as voiced in the following words: "The usage of the south drive from the Stanyan-street entrance before 7 A. M. only." Only members of the club presenting proper credentials could enjoy even this small privilege of rising in the small hours of the morning, riding some three miles to enter the Park, and then be out of it by 7 o'clock.

But the wheelmen appreciated the concession, and constituted themselves special policemen to exclude intruders, whose acts might possibly injure the freedom of legitimate riders, for the rules of the concession were rigidly observed and such was their conduct that before long the privileges were extended. The club by this time was in a flourishing financial condition and was constantly increasing in membership. Every member had his own machine and every machine was pedigreed.

Finally a rival to the San Francisco Cycle Club sprang into existence. This was the Bay City Wheelmen and it needed just this incentive to raise enthusiasm to the highest pitch. Each man was eager to find opportunities for the keenest rivalry, for the honor of his club was at stake, and in those days wheeling was a clean sport. Sport for the true love of sport. There were none of the sordid motives which follow in the train of professionalism. To become a professional was to place one's self outside of the social pale.

Money was repeatedly offered to the local wheelmen to induce them to enter a professional race, but the efforts were of no avail. If money were the trophy won in a contest it was immediately turned over to charity.

Eggers' Famous Record Mile.

With the existence of two clubs, record time-makers sprang into being. The first recorded time was made by Herman C. Eggers of the San Francisco Bicycle Club on November 24, 1881. It was a mile in 3:15, made on the old Bay District track, then used for horse racing. The track was in consequence softly rolled. No cinder tracks such as modern cyclists use could be found then.

Eggers' record stood for five years, for besides making the first recorded time, he went to the front with flying colors in the first three-day contest ever held in San Francisco. There has never been one in which greater interest was displayed. It began November 29th, and ended December 2d. The men entered were Bennett, Merrill, Boyston, Eggers and Dunbar. The entrance fee was $50 and the trophy $500.

Eggers was the newest rider having ridden only nine months at the time of entering for this race, and he had not had the proper training; nevertheless, he made 546 1-6 miles in those three days, resting but three hours and a half the entire time.

"Don't forget that one-sixth," Eggers said. “It was worse than the whole 500." In this race he beat F. C. Merrill, [maybe Fred T. Merrill] a professional, by thirty-one miles, and the $500 was donated to the charitable institutions of San Francisco; but he was the victim of an exceedingly undesirable state of affairs. Having entered the race against a professional he became one himself, which was the last thing he wished and which he tried earnestly to alter. He had not counted the full cost of that race. However, his fellow clubmen took up the matter for him, and appealed to the National Association of Wheelmen [maybe this is the League of American Wheelmen?] to have the title set aside. The Olympic Club also came to the rescue, and owing to their combined efforts, Eggers was reinstated in the club as an amateur, to his own delight and that of his friends, although the National League took pains to state that it was the last petition of its kind that would be considered by them under any circumstances.

Fred Russ Cook lowered Eggers' record to 3:05, which time was lowered in turn by Frank D. Elwell, who made a mlle in 2:49.

|

|

F. D. ELWELL WJO WON 20 OUT OF 21 RACES MAKING THE HIGHEST PERCENTAGE EVER HELD |

Elwell's Highest Percentage,

The pioneer wheelmen claim that Elwell holds the highest percentage of any rider in the world, having ridden in twenty-one races, and having won twenty first and one second prize. The first modern bicycle track was designed by him and was laid at Central Park. It was the first track using an easement curve permitting the rider to merge into the curve without too great a transition and was regarded as a great curiosity. The principles employed in its construction have been universally adopted.

It was not until the advent of the "safety" that the old "Neckbreaker" met its doom. But it came swift and sure, and was simply an example of the "survival of the fittest." The San Francisco Bicycle Club, which had seen and watched its inception, became incorporated with the Bay City Wheelmen, and professional riders soon pushed the amateurs to the wall. The pioneer wheelmen dropped out one by one, and pursued their sport as individuals. They are long-lived and still enthusiasts over the wheel. They have forged to the front in other undertakings than that of wheeling, but the reminiscences of those pioneer days are dear to their souls. IDA L. HOWARD.

Comments

Post a Comment