Picnic Trains to Redwood Canyon, part 1 16 Jun 1968, Sun

Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California) Newspapers.com

Picnic Trains to Redwood Canyon, part 1 16 Jun 1968, Sun

Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California) Newspapers.com

Picnic Trains to Redwood Canyon, part 2 16 Jun 1968, Sun

Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California) Newspapers.com

Picnic Trains to Redwood Canyon, part 2 16 Jun 1968, Sun

Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California) Newspapers.com

Picnic Trains to Redwood Canyon

THERE was something about boarding the coaches of the old

Oakland, Antioch & Eastern

electric line and heading for a picnic out among the gloriously secluded and

shaded glens and dales of

Redwood Canyon

that has left an indelible impression with Oakland rail historian

Vernon Sappers.

"It was only a short ride via the electric trains, but always a thrilling

expedition," Vernon tells us. "It attracted thousands of picnickers during the

early years of this century and even on up to the 1930s after the electric

line boasted the more modern appellation of

Sacramento Northern.

"Beautiful Redwood Canyon actually linked Oakland and its environs with Contra

Costa County, but the picnic areas were chiefly on the Contra Costa side. It

was one of the wonders of the west for visitors to discover Oakland so close

to a peaceful grove of towering redwood trees.”

The history of Redwood Canyon is equally engaging.

The canyon's redwood trees long ago played an important role in the

upbuilding of San Francisco as well as Oakland. For several years there was an annual cry of "fire" in San Francisco,

making that city's needs in the 1850s much more demanding. Several mills were

operating among redwood groves here as late as the 1870s and 1880s. Redwood

logs cut to size by mills nestled back in the canyon had to be hauled up over

the steep grades, first by oxen and then by mules and horses. If only they had

a railroad then it wouldn't have been so burdensome to get the huge logs to

the planing mills along the Oakland estuary and across the bay in San

Francisco.

|

|

From the photo collection of Vernon Sappers

|

|

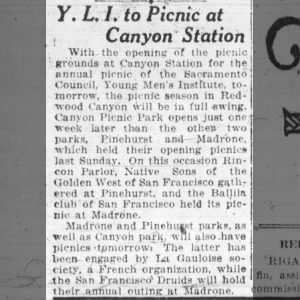

Conductor J. C. Obenchain (left), Brakeman C. E. Gsell (right) and

Superintendent of Equipment F. A. Miller in the Engine cab of a 1920

Oakland, Antioch & Eastern Picnic Special ready to leave the station

at 40th Street and Shafter Avenue with

California Cotton Mill employees

|

SEVERAL dairy farms also dotted this redwood country, and there were patches

of grazing-land for the milk herds as well as stacks of clover and alfalfa hay

wherever cultivation was possible. Even Redwood Canyon's water supply was

diverted for use by the ever-growing number of residents in Oakland. Testimony

as to the importance of the region as a water shed remains today with the land

holdings of the

East Bay Municipal Utility District still used for water supply.

Looking back to the year 1913 Vernon Sappers continues to enthuse over the

beauty and peace then found in the wilderness area our bay region populace

were discovering via rail in Redwood Canyon. "Not that it hadn't had its share

of visitors prior to this," he says. "In the early years there were a lot of

folks who hiked through Redwood Canyon, and there was always the horse and

buggy, and eventually the ancient model automobiles. But before you started

out by auto you had to be sure that old antique could climb

the steep grades."

All of which made it most convenient to "take the train."

"Ready and willing to supply train service was the Oakland, Antioch &

Eastern Railway that would become the Sacramento Short Line and eventually

the Sacramento Northern. This railroad maintained a special department for

years that planned and managed 'Picnic Specials' as well as other excursion

trains. It was headed by L. H. Rodebaugh.

"It was the Oakland, Antioch & Eastern that established the picnic parks

in Redwood Canyon. Largest and most popular was, the one called

Pinehurst Park. The others were Madrone Park, Canyon, and Sequoyah. Each park was equipped with all the necessities needed at such picnic

grounds. But at Pinehurst there was even a Merry-Go-Round for the children,

a dance pavilion, baseball diamond and band stand in addition to the picnic

tables, benches and fire pits.

"If that doesn't bring on nostalgia, think of those lovely hiking trails

that climbed up through the stands of redwood studding the canyon

hillsides."

The Oakland, Antioch & Eastern advertised this paradise as the

"Adirondak Mountains of the Pacific."

REDWOOD Canyon's picnic season usually began the later part of April and

lasts through September. Fraternal groups, service clubs, industrial firms,

department stores, social clubs, Sunday school and church groups -

everybody, it seemed - sponsored picnics in Redwood Canyon. They came from

as far as Sacramento, chartering the trains of the Oakland, Antioch &

Eastern.

"So popular was this service by the O.A.&E. that it became necessary to

make picnic arrangements well in advance," Vernon relates. "It was the only

way you could be assured of a 'Picnic Special.'

“The railroad provided special round trip fares, advertised not only in the

newspapers but on billboards. In most instances the fares quoted were from

the San Francisco Ferry Building and included the ferry steamer ride across

San Francisco Bay to the

Key Route Pier terminal where the ‘Picnic Special'

would be waiting. But there was a trick to this that we'll explain later.

"The swarm of picnickers every weekend was good evidence of the efficient

work by General Passenger Agent Rodebaugh and his aides. Among his Traveling

Passenger Agents were C. H. James and Hugo Arnstein, the latter a brother of

Walter Arnstein, president of the railroad.

"The 'Picnic Specials,' of course, were operated as special trains. They

never appeared on the timetable schedules, although some were operated as

special sections of a regular train. Sometimes there were even second and

third sections to take care of the crowd.

SUCH heavy movement of picnic trains naturally brought a demand for extra

cars. "In 1913 the Oakland, Antioch & Eastern bought from Southern

Pacific some of their old wooden passenger coaches that had been used on

SP's local suburban lines and were looked on as surplus equipment by the

friendly railroad.

“Although they lacked the interior appointments and riding qualities that

the O. A. & E. standard coaches afforded, the management tagged them as

'Deluxe' cars. They were far from being deluxe, and the regular service

passengers complained frequently about the rough rides in hard seats.

THE time finally came when trailer coaches were added to the pool of

"deluxe" cars. One of these was a second-hand

Pennsylvania Railroad coach,

numbered 1207. Three others were bought from the

Ocean Shore Railroad and

numbered 1208, 1209 and 1210. They were attractive cars when rebuilt and

frequently used in regular passenger service and on the school trains.

"But, even with these additions there weren't enough coaches to handle the

picnic hordes that would gather at

40th and Shafter on weekends ready to hit

the Redwood Canyon trail. On many occasions the O. A. & E. had to rent

cars from the

Key Route. These were the short trailer coaches numbered from

541 to 550.

"In order to use such short trailer coaches on the O. A. & E. it was

necessary to block up their bolsters so that the couplers would be the same

height as the O. A. & E. cars. It was a matter of six inches. The work

was usually performed at the shops late Saturday in order to have the cars

ready for service the next morning. On Sunday night the work had to be

undone and the cars returned to the Key Route. Oakland, Antioch &

Eastern paid the Key Route a flat rental of $2.50 per car per day.”

|

|

From the photo collection of Vernon Sappers

|

|

Oakland, Antioch & Eastern Picnic Special on siding in Redwood

Canyon's Parkhurst Park in 1914

|

WHEN traffic became unusually heavy the O. A. & E. would borrow trailer

coaches from their connecting line in Sacramento - the Northern Electric

Railway that operated up the Sacramento Valley to Chico.

"The Key Route cars were usually hauled by two 'Box Moters,' numbered 101

and 102," Vernon continues. "It wasn't unusual though to find Box Moters

numbers 1001 and 1002 on the O. A. & E. line out of Oakland, both

borrowed from their branch line. Because the electric locomotives 103 and

104 were originally designed to haul passenger trains before they became

freight locomotives, they too were frequently pressed into service.

"Key Route freight locomotive No. 1001 frequently pulled Key coaches from

the Pier terminal on weekends when travel was heavy. This was due to the

fact that O. A. & E. could not run their heavy freight engines over the

Key Trestle to the Pier. Their weight made it too hazardous. So Key Route's

1001 would pull the 'Picnic Special' from the Pier to 40th and Shafter, then

cut off, and one of the O. A. & E. motors would couple in.

"This type of operation usually took place on a Fourth of July, Labor Day,

or Admission Day, when picnic travel was at its heaviest. Or when the State

Fair was running in Sacramento. Holidays such as those taxed the electric

line to its fullest capacity.

"Train crews were never given a day off or permitted to lay off on weekends

during the summer months. Even freight crews were pressed into service on

occasion. Brakemen performed extra duty as Helper Conductors in order to

have manpower to pick up fares.”

PICNIC trains were made up with as many as 10 cars and as few as four. Box

motors 101 and 102 were equipped with wooden benches to provide additional

seating for passengers should the emergency demand.

“When all the passengers were discharged at the various stations in Redwood

Canyon the empty trains would turn back to the Oakland depot for another

load. The run to Canyon station took but 20 minutes; to Pinehurst Park

station 25 minutes.

"Some of the trains would lay over on the long siding at Pinehurst while

others might go on and tie up at

Burton station between Moraga and Lafayette

(which had a long siding). Should Burton station fill up the trains would go

on to

Concord and stand by on a siding there.

"Even with all this heavy traffic there was never an accident in all the

years the Oakland, Antioch & Eastern operated those picnic trains.”

Vernon credits the record to an efficient automatic block signal system the

electric line installed early in its operation, as well as to the efficiency

of the train crews.

A few of those trainmen are still living.

"The oldest in years is Ernest Knoblock, better known to his passengers as

“Knobby. He is now 94 and lives in Santa Cruz,” Vernon reports. Among the

others are J. C. Obenchain, W. T. Van Cleave and S. R. Bowman, now residents

of Sacramento, Lynn Hall of Walnut Creek, Oscar Schindler of Pittsburg, and

Karl Rodebaugh of Lafayette.

"In the ticket office were Roy Sneider, still a resident of Oakland. One of

the brakemen who later became a towerman was Leslie Olsen who remains an

Oakland resident.

“There may be others still living that I have overlooked. If so, it would be

nice to hear from them."

It's all only a pleasant memory now. Only those who rode the Oakland,

Antioch & Eastern out into the wilderness of the “Adirondaks of the

Pacific" have any idea of the happy, carefree days Vernon Sappers describes

here as a way of life never again to be enjoyed.

Comments

Post a Comment