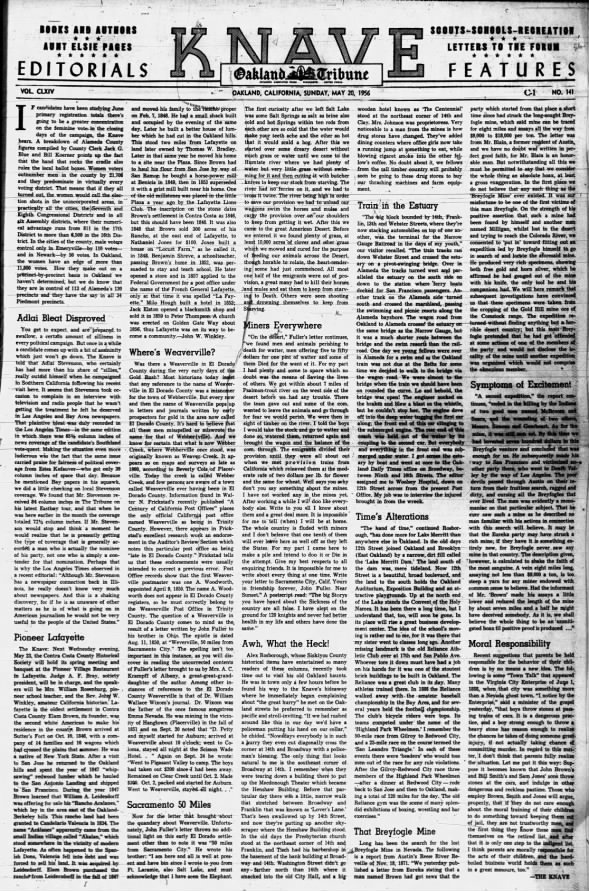

Pioneer Lafayette

The Knave: Next Wednesday evening, May 23, the

Contra Costa County Historical Society

will hold its spring meeting and banquet at the Pioneer Village Restaurant

in Lafayette. Judge

A F. Bray, society president, will be in charge, and the speakers will be Mrs.

William Rosenburg,

[Margaret Jennie Bickerstaff Rosenberg]

pioneer school teacher, and the Rev.

John W. Winkley, amateur California historian.

Lafayette

is the oldest settlement in Contra Costa County.

Elam Brown, its founder, was the second white American to make his residence in the

county. Brown arrived at

Sutter's Fort on

Oct. 10. 1846, with a company of 24 families and 16 wagons which had crossed

the plains that summer. He was a native of New York State. After a visit to

San Jose he returned to the Oakland hills and spent the year of 1847

whipsawing redwood lumber

which he hauled to the

San Antonio Landing and

shipped to San Francisco. During the year 1847 Brown learned that

William A. Leidesdorff

was offering for sale his "Rancho Acalanes," which lay in the area east of the Oakland-Berkeley hills. This rancho

land had been granted to

Candelario Valencia

in 1834.

The name "Acàlanes" apparently came from the small Indian village called

"Akalan which stood somewhere in the vicinity of modern Lafayette.

As often happened to the Spanish Dons, Valencia fell into debt and was

forced to sell his land. It was acquired by Leidesdorff. Elam Brown purchased the rancho from

Leidersdorff in the fall of 1847 and moved his family to the rancho proper

on Feb. 7, 1848. He had a small shack built and occupied by the evening of

the same day. Later he built a better house of lumber which he had cut in

the Oakland hills. This stood two miles from Lafayette on land later owned

by

Thomas W. Bradley. Later in that same year he moved his home to a site near the

Plaza. Since Brown had to haul his flour from San Jose by way of San Ramon he

bought a horse-power mill at

Benicia in

1849, then in 1853 superseded it with a grist mill built near his home. One

of the old millstones was placed in the little Plaza a year ago by the

Lafayette Lions Club. The inscription on the stone dates Brown's settlement

in Contra Costa as 1846, but this should have been 1848. It was also 1848

that Brown sold 300 acres of his Rancho, at the east end of Lafayette, to

Nathaniel Jones for $100. Jones built a house

on "Locust Farm," as he called it, in 1848.

Benjamin Shreve, a schoolteacher, passing Brown's home in 1852, was persuaded to stay and

teach school. He later opened a store and in 1857 applied to the Federal

Government for a post office under the name of the French General

Lafayette, only at that time it was spelled “La Fayette."

Milo Hough

built a hotel in 1853;

Jack Elston

opened a blacksmith shop and sold it in 1859 to

Peter Thompson: A church was erected on Golden Gate Way about 1856, thus Lafayette was on

its way to become a community. - John W. Winkley.

See also:

- Redwoods Atop Oakland Hills First Brought Settlers Here - Oakland Tribune - 09 Oct 1966, Sun - Page 137

- Knave: Potter Elk Horn, Redwood Canyon, Redwood Regional Park, Mariano Vallejo

- Knave - Oakland Tribune, 03 Mar 1940 - 'Acalanes'

- Knave: The Spanish Settlers, El Rancho de Laguna de Palos Colorados - Oakland Tribune, 19 Nov 1933

- Knave - Oakland Tribune,14 Oct 1956 - Contra Costa

Where's Weaverville?

Was there a

Weaverville in El Dorado County

during the very early days of the Gold Rush? Most historians today insist

that any reference to the name of Weaverville in El Dorado County was a

misnomer for the town of Webberville. But every now and then the name of

Weaverville pops up in letters and journals written by early prospectors for

gold in the area now called El Dorado County. It's hard to believe that all

these men misspelled or miswrote the name for that of Webber(ville). And we

know for certain that what is now

Webber Creek, where

Webberville once stood, was originally known as Weaver Creek. It appears so

on maps and surveys as late as 1860, according to

Beverly Cola of Placerville. Today the creek is called Webber Creek, and few persons are aware of a

town called Weaverville ever having been in El Dorado County. Information

found in

Walter N. Frickstad's

recently published "A Century of California Post Offices" places the only official California post office named Weaverville as

being in Trinity County. However, there appears in Frickstad's excellent

research work an endorsement in the Auditor's Review Section which notes

this particular post office as being "late in El Dorado County." Frickstad

tells us that these endorsements were usually intended to correct a previous

error. Post Office records show that the first Weaverville postmaster was

one A. Woodworth, appointed April 9, 1850. The name A. Woodworth does not

appear in El Dorado County registers, so he must correctly belong to the

Weaverville Post Office in Trinity County. The question of a Weaverville in

El Dorado County comes to mind as the result of a letter written by

John Fuller

to his

brother

in Ohio. The epistle is dated Aug. 11, 1850, at "Weverville, 50 miles from

Sacramento City.” The spelling isn't too important in this instance, as you

will discover in reading the uncorrected contents of Fuller's letter brought

to us by

Mrs. A. C. Krampff

of Albany, a great-great-granddaughter of the author. Among other instances

of references to the El Dorado County Weaverville is that of

Dr. William Wallace Wixom's journal. Dr. Wixom was the father of the once famous songstress

Emma Nevada. He was

mining in the vicinity of

Hangtown

(Placerville) in the fall of 1851 and on Sept. 20 noted that "D. Petty and

myself started for Auburn; arrived at Weaverville about 10 o'clock; went to

Coloma, stayed all night at the Scisson Wade Hotel." Again on Sept. 24 he

wrote: "Went to Pleasant Valley to camp. The boys had taken out $200 since

had been away. Remained on Clear Creek until Oct. 2. Made $300. Oct. 2,

packed and started for Auburn. Went to Weaverville, stayed all night..."

Sacramento 50 Miles

Now for the letter thật brought about the quandary about Weaverville.

Unfortunately, John Fuller's letter throws no additional light on this early

El Dorado settlement other than to note it was "50 miles from Sacramento

City." He wrote his brother: "I am here and all is well at present and have

bin since I wrote to you from Ft Laramie, also Salt Lake, and must

acknowledge that I have seen the Elephant. The first curiosity after we left

Salt Lake was some Salt Springs as salt as brine also cold and hot Springs

within ten rods from each other are so cold that the water would make your

teeth ache and the other so hot that it would scald a hog. After this we

started over some dreary desert without much grass or water until we came to

the Humtate river where we had plenty of water but very little grass without

swimming for it and then cutting it with butcher knives to keep our stock

from starving. The river had no ferries on it, and we had to cross it twice.

The river being high in order to save our provision we had to unload our

waggons swim the horses and mules and carry the provision over on our

shoulders to keep from getting it wet. After this we came to the great

American Desert. Before we entered it we found plenty of grass, at least

10,000 acres of clover and other grass which we mowed and cured for the

purpose of feeding our animals across the Desert, though horable to relate,

the heart-rendereing scene had just commenced. All most one half of the

emigrants were out of provision, a great many had to kill their horses and

mules and eat them to keep from starving to Death. Others were seen shooting

and drowning themselves to keep from Starving.

Miners Everywhere

“On the desert," Fuller's letter continues, "we found men and animals

perishing to death for watter, men offering five to fifty dollars for one

pint of watter and some of them Died for the want of it. For my part

I had plenty and some to spare which no doubt was the means of Saving the

lives of others. We got within about 7 miles of Psalmon-trout river on the

west side of the desert before we had any trouble. There the team gave out

and some of the com. wanted to leave the animals and go through for fear we

would perish. We were then in sight of timber on the river. I told the boys

I would take the stock and go to watter and done so, watered them, returned

again and brought the wagon and the balance of the com. through. The

emigrants divided their provision until they were all about out when we met

provision trains from California which releaved them at the moderate rate of

two dollars per lb. for flower and the same for wheat. Well says you why

don't you say something about the mines. I have not worked any in the mines

yet. After working a while I will doo like everybody else. Write to you all

I know about them and a great deal more. It is impossible for me to tell

(when) I will be at home. The whole country is fluded with miners and I

don't beleave that one tenth of them will ever leave here as well off as

they left the States. For my part I came here to make a pile and intend to

doo it or Die in the attempt. Give my best respects to all enquiring

friends. It is impossible for me to write about every thing at one time.

Write your letter to Sacramento City, Calif. Yours in friendship forever,

John Fuller. Near Sunset." A postscript read: “The big Storys you have heard

about the Sickness of the country are all false. I have slept on the

ground for 120 knights and never had better health in my life and others

have done the same."

Awh, What the Heck!

Alex Rosborough, whose

Siskiyou County historical items

have entertained so many readers of these columns, recently took time out to

visit his old Oakland haunts. He was in town only a few hours before he

found his way to the

Knave's

hideaway where he immediately began complaining about "the great hurry" he

met on the Oakland streets he preferred to remember as pacific and

stroll-inviting. "If we had rushed around like this in our day we'd have a

policeman putting his hand on our collar," he chided. “Nowadays everybody is

in such a hurry they even cut diagonally cross the corner at

14th and Broadway with a

policeman's blessing. The only thing that looks natural to me is the

southeast corner of Broadway at 14th. I remember when they were tearing down

a building there to put up the

Macdonough Theater

which became the

Henshaw Building.

Before that particular day there was a little, narrow walk that stretched

between Broadway and Franklin that was known as 'Lover's Lane.' That's been

swallowed up by 14th Street, and now they're putting up another skyscraper

where the Henshaw Building stood. In the old days

the Presbyterian church stood at the northeast corner of 14th and

Franklin, and

Tisch had his barbershop

in the basement of the bank building at Broadway and 14th.

Washington Street didn't go any-farther north than 14th where it smacked

into the old City Hall, and a big wooden hotel known as "The Centennial" stood at the northeast corner of 14th and Clay. Mrs. Johnson was

proprietoress. Very noticeable to a man from the mines is how drug stores

have changed. They've added dining counters where office girls now take a

running jump at something to eat, while blowing cigaret smoke into the other

fellow's coffee. No doubt about it, we fellows from the tall timber country

will probably soon be going to these drug stores to buy our thrashing

machines and farm equipment.

Train in the Estuary

"The big block bounded by 14th, Franklin, 13th and Webster Streets, where

they're now stacking automobiles on top of one another, was the terminal

for the Narrow Gauge Railroad in the days of my youth," our visitor recalled. "The train tracks ran down Webster Street and

crossed the estuary on a pivot-swinging bridge.

Over in Alameda the tracks turned west and paralleled the estuary on the

south side on down to the station where ferry boats docked for San

Francisco passengers. Another track on the Alameda side turned south and crossed the marshland,

passing the swimming and picnic resorts along the Alameda bayshore. The

wagon road from Oakland to Alameda crossed the estuary on the same bridge as

the Narrow Gauge, but it was a much shorter route between the bridge and the

swim resorts

than the railroad. One day we young fellows were over in Alameda for a swim

and as the Oakland train was not due at the

Baths for some time we

decided to walk to the bridge via the wagon road. We were almost to the

bridge when the train we should have been on rounded the curve. Lo and

behold, the bridge was open! The engineer socked on the brakes and blew a

blast on the whistle, but he couldn't stop her. The engine dove off into the

deep water tugging the first car along; the front end of this car clinging

to the submerged engine. The rear end of this coach was held out of the

water by its coupling to the second car. But everybody and everything in the

front end was submerged under water. I got across the estuary by boat and

went at once to the

Oakland Daily Times

office on Broadway, between Ninth and 10th Streets. The editor assigned me

to Woolsey Hospital,

down on 12th Street across from the present Post Office. My job was to

interview the injured brought in from the wreck.

Time's Alterations

"The hand of time," continued Rosborough, "has done more for Lake Merritt

than anywhere else in Oakland. In the old days

12th Street joined Oakland and Brooklyn (East Oakland) by a narrow, dirt

fill called the 'Lake Merritt Dam.'

The land south of the dam was mere tideland. Now 12th Street is a beautiful,

broad boulevard, and the land to the south holds the Oakland Auditorium,

Exposition Building and an attractive playgrounds. Up at the north end of

the Lake stands the

Convent of the Holy Names. It has been there a long time, but I understand that, too, will soon be

gone. In its place will rise a great business development center. The idea

of the school's moving is rather sad to me, for it was there that my sister

went to classes long ago. Another missing landmark is the old

Reliance Athletic Club

over at

17th and San Pablo Ave.

Whoever tore it down must have had a job on his hands for it was one of the

stoutest brick buildings to be built in Oakland. The Reliance was a great

club in its day. Many athletes trained there. In

1888 the Reliance walked away with the amateur baseball championship

in the Bay Area, and for several years held the football championship. The

club's

bicycle riders were tops. Its teams competed under the name of the 'Highland Park Wheelmen.' I remember

the 50-mile race from Gilroy to Redwood City, and a 25-mile race on the course termed the 'San Leandro Triangle." In each of these events there were 'headers' who would toss men out of

the race for any

rule violations.

After the

Gilroy-Redwood City

race three members of the Highland Park Wheelmen - after a dinner at Redwood

City - rode back to San Jose and then to Oakland, making a total of 120

miles for the day. The old Reliance gym was the scene of many splendid

exhibitions of boxing, wrestling and bar exercises."

See also:

That Breyfogle Mine

Long has been the search for the lost

Breyfogle Mine

in Nevada. The following is a report from Austin's

Reese River Reveille

of Nov. 18, 1871. "We yesterday published a letter from Eureka stating that

a man named Brown had got news that the party which started from that place

a short time since had struck the long-sought Breyfogle mine, which said

mine can be traced for eight miles and assays all the way from $9,000 to

$18,000 per ton. The letter was from Mr. Blain, a former resident of Austin,

and we have no doubt was written in perfeet good faith, for Mr. Blain is an

honorable man. But notwithstanding all this we

must be permitted to say that we consider the whole thing an absolute hoax,

at least a gross exaggeration. In the first place we do not believe that any

such thing as the 'Breyfogle Mine' ever existed. It was our misfortune to be

one of the first victims of this man Breyfogle. On the strength of his

positive assertion that such a mine had been found by himself and another

man named Milligan, whilst lost in the desert and trying to reach the

Colorado River, we consented to 'put in' toward fitting out an expedition

led by Breyfogle himself to go in search of and locate the aforesaid mine.

He produced very rich specimens, showing both free gold and horn silver,

which he affirmed he had gouged out of the mine with his knife, the only

tool he and his companions had. We will here remark that subsequent

investigations have convinced us that these specimens were taken from the

cropping of the Gold Hill mine ore of the Comstock range. The expedition

returned without finding anything but a horrible desert country; but this

man Breyfogle pretended that he had got offended at some actions of one of

the members of the party and would not disclose the locality of the mine

until another expedition was organized which would not comprise the

obnoxious member.

Symptoms of Excitement

"A second expedition,” the report continues, "ended in the killing by the

Indians of two good men named McBroom and Sears, and the wounding of two

others, Messrs. Simons and Gearheart. As for the

mine, it was still non est. By this time we had invested seven hundred

dollars in this Breyfogle venture and concluded that was enough for us. He

subsequently made his way to San Francisco and victimized another party

there, who went to Death Valley by the way of Los Angeles. The poor devils

passed through Austin on their return from their fruitless search, ragged

and dirty, and cursing all the Breyfogles that ever lived. The man was

evidently a monomaniac on that particular subject. That he ever saw such a

mine as he described no man familiar with his actions in connection with

this search will believe. It may be that the Eureka party may have struck a

rich mine; if they have it is something entirely new, for Breyfogle never

saw any mine in that country. The description given, however, is calculated

to shake the faith of the most sanguine. A vein eight miles long, assaying

not less than $9.000 a ton, is too steep a yarn for any miner endowed with

common sense to believe. Had the informant of Mr. 'Brown' made his assays a

little lower and reduced the length of the mine by about seven miles and a

half he might have deceived somebody. As it is, we shall believe the whole

thing to be an unmitigated hoax til positive proof is produced ..."

|

|

1866-05-29 Reese River Reveille |

Moral Responsibility

Recent suggestions that parents be held responsible for the behavior of

their children is by no means a new idea. The following is some "Town Talk”

that appeared in the

Virginia City Enterprise

of June 1, 1888, when

that city was something more than a Nevada ghost town. "I notice by the Enterprise," said a minister of the gospel yesterday,

"that boys throw stones at passing trains of cars. It is a dangerous

practice, and a boy strong enough to throw a heavy stone has reason enough

to realize the chances he takes of doing someone great injury, if not

actually taking chance of committing murder. In regard to this matter, I

don't think that parents fully realize the situation. Let me put it this

way: Suppose it becomes known that John Brown's and Bill Smith's and Sam

Jones' sons throw stones at the cars, and indulge in other dangerous and

reckless pastime. Those who employ Brown, Smith and Jones will argue,

properly, that if they do not care enough about the moral training of their

children to do something toward keeping them out of jail, they are not

trustworthy men, and the first thing they know these men find themselves on

the retired list, and after that it is only one step to the indigent list. I

think parents are morally responsible for the acts of their children, and

the hardboiled business world holds them as such in a great measure, too."

Comments

Post a Comment